“We don’t have any more.”

It was one of those quotes that you knew, immediately, was going to have sticking power, and I can only presume Chicago Cubs owner and chairman Tom Ricketts regretted the phrasing as soon as he’d uttered it.

It was a February press conference, before the start of the 2019 season, and Ricketts was asked why the club hadn’t spent more aggressively in free agency. At a competitive time – for a team that would go on to miss the postseason for the first time in five years – why not spend more money?

“That’s a pretty easy question to answer,” Ricketts said at the time. “We don’t have any more.”

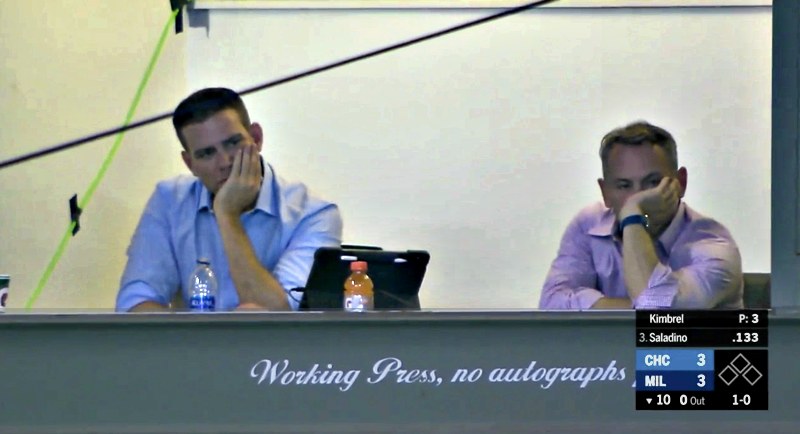

To be sure, hindsight would show there was a little gamesmanship there, as the Cubs did go on to add to payroll, both in the Craig Kimbrel signing (which was not entirely offset by Ben Zobrist’s absense) and the Nick Castellanos trade. But the general message was clear: the baseball budget had been expended, and the revenue coming in would support a payroll only at that second tier of the luxury tax.

Given that the level put the Cubs at the top of spending in all of baseball, I was probably less troubled by the pronouncement of no-more-money than much of the Cubs’ fan base. When the Cubs are well up into the luxury tax in payroll, I find criticisms of their “lack of spending” to be a lot less persuasive.

I mention all of that because, at present, the Cubs sit right around the first tier of the luxury tax, which would leave them a reasonable amount of flexibility if they were going to spend as much as they did last year (more than $20 million, to be precise). Revenues, I’d speculate, were probably pretty flat from the year before, and, with a new team-controlled TV deal on the way, with new luxury suites and seating areas coming on line, and with the pricey Wrigley renovation coming to a close, the longer-term revenue picture for the Cubs should be increasingly rosy.

And yet, we’re hearing the same plop from others around the game that we were hearing last year from those in the organization: there’s just no more money.

From Ken Rosenthal’s Winter Meetings preview this morning, a comment on the Cubs’ ability to spend: “Club officials are telling representatives of even low-budget free agents that they need to clear money before engaging in serious negotiations.”

Hey, that sounds annoyingly familiar – except this time around, the Cubs already have a payroll down multiple tens of millions of dollars from last year.

And the Cubs have to clear additional payroll before they can even negotiate with lesser free agents? I am sure the Cubs are indeed out there saying it if Rosenthal is reporting it, but is their claim actually true?

That would be an indefensible thing to be true unless the Cubs had been mandated to get payroll back under the $208 million luxury tax level for 2020. And, when you consider the modest implications of “repeat offender” status, getting under the luxury tax – entirely for its own purposes – would itself be an indefensible mandate if it were predicated on avoiding being a repeat offender.

To be sure, yes the Cubs absolutely *could* get back under the luxury tax next year if the simply strip away the departing contracts and make no significant additions, but let’s talk about the financial benefit of doing so (which is the only benefit at this stage in the penalty process): in a hypothetical world where the Cubs were willing to post a, say, $230 million payroll as a first-time offender, but wouldn’t be willing to do so as a second-time offender, the tax difference between the first and second year is a whopping $2.2 million. That’s it. The tax rate the first time around is 20% on the overage in the first tier (and *only* the overage). The tax rate the second year on the overage is 30%. At a reasonable luxury tax payroll level, that difference in tax is *NOTHING,* and absolutely SHOULD NOT be a consideration on how the Cubs choose to spend this offseason.

If there are broader limitations on spending that the Cubs want to try to sell to the public, then, by all means, let’s have those discussion and analyze them in a fair way. I’m open to it. But what I am not open to is any conversation that starts with “well, the Cubs have to get back under the luxury tax because being a repeat offender is so terrible.” It’s not. Stop. Do not go there.

If there are bigger revenue problems that dictate lower spending? If there are huge commitments the Cubs want to make to players already under control? If there is a plan to more aggressively target free agents in next year’s class? Those are all conversations I’m at least open to having. Just don’t get me started on the repeat offender stuff.

So anyway, here’s where we leave this: we know that the Cubs aren’t always forthright with their spending plans, and that’s for understandable reasons. We also know that, with pieces they may want to trade first, the free agents they target might change dramatically based on what trades they’re able to pull off – so holding back right now makes sense in any case. And it’s also true that, in this particular free agent market, we endorse the Cubs kinda waiting back, trying to make additive trades first, and then going over the later signings to take some swings.

In other words, it’s not actually all that inconsistent with what we want to see from the Cubs this offseason to have them out there telling agents they can’t negotiate on lesser deals right now, and they can offer up whatever reason they like. I’m just saying I’m considerably less cool with it if the *actual* reason they cannot negotiate on those deals right now is because the budget (1) is reduced, and (2) is fully committed. Eff that.

I’m not sure we’re actually going to know the answers to all of this until we gain some hindsight ability to look back. It’s long been the case that we weren’t expecting the Cubs to be aggressive on the top free agents in this class, but it would be something else entirely if, at the end of this offseason, it’s clear that the intention was to get under the luxury tax. It would cast reports like today’s in an entirely different light.

For now, I’ll give a little benefit of the doubt, and proceed to observe the Cubs’ offseason through the lens I mentioned above: I think exploring trades (both moving out, and moving in) is how the Cubs should be attacking this market, and then after that process is complete or reaches a point where you know additional moves are unlikely, then make shorter-term, lower-cost additions in free agency. It’s a deep market in the areas the Cubs have needs (particularly among starting pitchers and among roll-the-dice relievers), so the good and sage approach is also consistent with not going out there and spending $30 million right away on a couple years of a mid-tier starting pitcher. If, in hindsight, we can see that’s really all the Cubs were doing, then fine, I got no beef with reports like today’s.

We’ll see, though.