I understand the impetus, as Heyward’s offensive struggles are deep and profound, and he came to the Cubs as a very high-profile addition. The 26-year-old is hitting .228/.316/.316 with a 74 wRC+, by far the worst performance of his career, and among the worst half a dozen performances in the National League. That’s scary bad. The glove is still phenomenal – so much so that it’s not like I’m in favor of benching the guy at this point – but it’s fair if you’re unnerved by the bat.

Equally scary is that the genesis of the low batting average and power, which together drive much of the poor results, does not appear to be entirely flukey. Though you may attribute it to too many groundballs, it’s not the groundball rate, alone, that is a problem (Heyward’s 48.7% groundball rate is only slightly higher than league average (45.0%) and is actually lower than his career mark (49.8%)). And groundballs, well struck, do not leave you with a nearly unplayable .273 batting average on balls in play.

Instead, the problem is even simpler, and you’ve seen it: he’s just not hitting the ball very hard.[adinserter block=”1″]

Sometimes our eyes lie, but on this front, the data backs it up. Consider that Heyward’s soft contact rate (27.2%) is his highest since 2011, and his hard contact rate (25.4%) is also his lowest since 2011. That hard contact rate is the 13th lowest in baseball right now. The soft contact rate? It’s the worst in baseball.

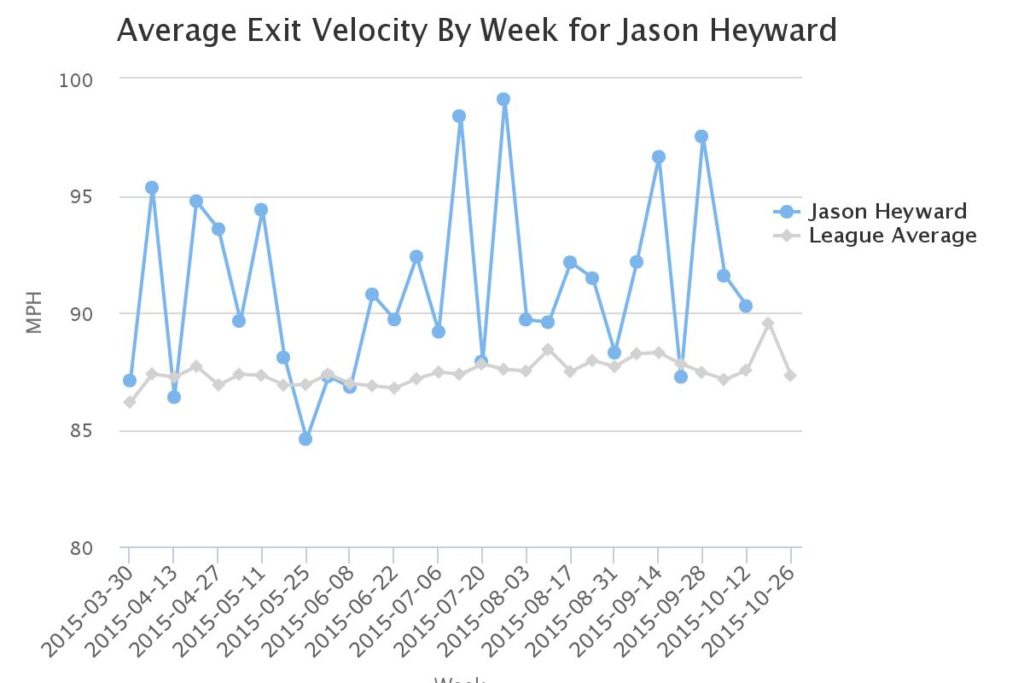

Take a look at Heyward’s exit velocity from 2015 (via Baseball Savant):

And, standing in very stark contrast, from 2016:

Heyward was consistently above average last year (even if last year’s average exit velocity had been as high as it is around baseball this year (interesting aside), he still would have consistently been topping it), and is consistently below average this year. Because exit velocity is correlated with hits and power, this significant drop is undoubtedly a part of why his results aren’t there.[adinserter block=”2″]

So it’s not just a matter of Heyward hitting a lot of groundballs. In fact, he’s pretty clearly trying to elevate the ball more, which was something we discussed at length in the offseason. Problem is, when you’re trying to elevate and you aren’t hitting the ball with authority, you get a lot of pop-ups, which are essentially as bad as strikeouts, because they never have a chance to become hits. Heyward’s 16.9% infield fly rate is, once again, his highest since 2011*, and is the sixth highest in baseball. Worse, the batters ahead of him are all guys you’d expect to see at the top of the list, and/or could easily live with it because either they hit an extremely small volume of fly balls overall or they’re sluggers who are trying to elevate and go deep (and frequently succeed).

You may recall discussion before the season about wanting Heyward, with his large build and long levers, to elevate the ball more to take advantage of his theoretically natural power. It is working in the sense that Heyward’s fly ball rate is up almost seven percentage points from last year, but, because he is not consistently striking the ball with authority, the increase in fly balls hasn’t really helped anything. Heyward’s .088 ISO is by far the lowest of his career, barely half his career mark, and seventh lowest in baseball (I warn you, don’t look at that list unless you want to become rather uncomfortable).

Wrist injuries are notorious for sapping a hitter’s ability to hit the ball with maximum authority, and we know that Heyward was dealing with a wrist injury for some time earlier this year (he mentioned at the All-Star break that he tried to play through it earlier in the season, though it’s not entirely clear whether he was still feeling discomfort after returning from getting a few days off in early May to rest it). I’m not going to speculate on injuries, and we’ve been given no indication that the discomfort persists to this day.

Whatever the reason – be it a cause or a result – not hitting the ball with authority, coupled with apparent adjustments the Cubs and Heyward (rightly) worked on before the season to have him elevate the ball more are actually having a disastrous effect on the results he’s getting. That doesn’t mean the adjustments were bad or cannot take hold with more time, but a guy hitting the ball as softly as Heyward is right now is not someone you want to see throwing his (already complicated) swing out of whack to try and elevate the ball. When he succeeds, he’s getting a ton of pop ups and weak fly balls. When he doesn’t, he’s getting other kinds of weak contact.[adinserter block=”3″]

But, are things at least getting better? Is there hope for more improvement in the second half?

Yes, of course! I’m an optimistic person! I wouldn’t leave you hanging like that!

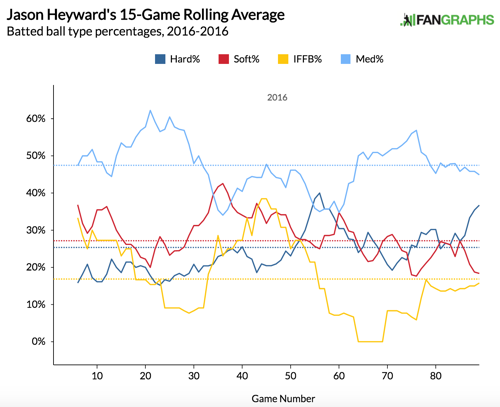

If you stretch a bit, you can see perhaps some improvement in the exit velocity chart above in June and July, and there’s also this (via FanGraphs’ excellent graphing feature):

Starting right around game 50, which was June 8, you can see a dramatic drop in the infield fly ball rate, a steady decline in the soft contact, a plateauing in the hard contact rate (which was way up from the start of the year at that point), and a return in medium contact (largely at the expense of that soft contact). There are legitimately good signs there!

So, surely Heyward’s results are much better from June 8th on, right? Well, he’s hitting .238/.315/.325 in that stretch, and the numbers pretty much match his season numbers across the board. HOWEVA, the soft contact is way down, the hard contact is way up, the infield fly ball rate is way down, and the groundball rate is flat.

If those trends continue, the results will soon follow. What we may be seeing in these numbers is a manifestation of what, for one example, Joe Maddon has been saying a lot for the past month and a half: Heyward’s hitting the ball hard, he’s just hitting it at people. I suspect, for many of you, your gut just won’t believe it. But, hey, the data is the data.

When considering it all, I see a hitter who had some issues because of a wrist injury, who probably isn’t getting the results that certain swing changes were designed to produce, who isn’t making the kind of hard contact he has through his career, and who is also suffering through some bad luck. The results have not been better lately, but the underlying batted ball data has been. The latter predicts the future slightly better than the former, so maybe there is hope for a rebound in the coming months.

I think we should be realistic on that front, and perhaps not hope for an offensive force, but there are reasons to believe Heyward can at least be an average hitter for the rest of the year. And then, from there, hopefully with an offseason to reset, re-evaluate, etc., he can get back on track (which is what happened, incidentally, in 2011*).

*(There are so many parallels in the numbers between this year and 2011, the season after Heyward’s impressive rookie debut, right down to an apparent attempt to elevate the ball more. That would make some sense, given that everyone’s been trying to get more power out of Heyward’s huge build, and his sophomore season would include a number of adjustments as well. Perhaps the Braves tried something similar to what the Cubs are trying now. Perhaps it didn’t work. (That season also included a Spring Training shoulder injury that lingered until he was put on the DL in May for a bit. Again, so many parallels to this year.))